During World War II, over 2.5 million African American men signed up for the draft, of which 1.2 million served in uniform. However, the services were still segregated at this time, despite pressure from civil rights leaders for integration. Thus, Black men enlisting in the service faced substandard training, inferior barracks and recreational facilities, and discrimination from staff and personnel, in addition to the regular hazards of service.

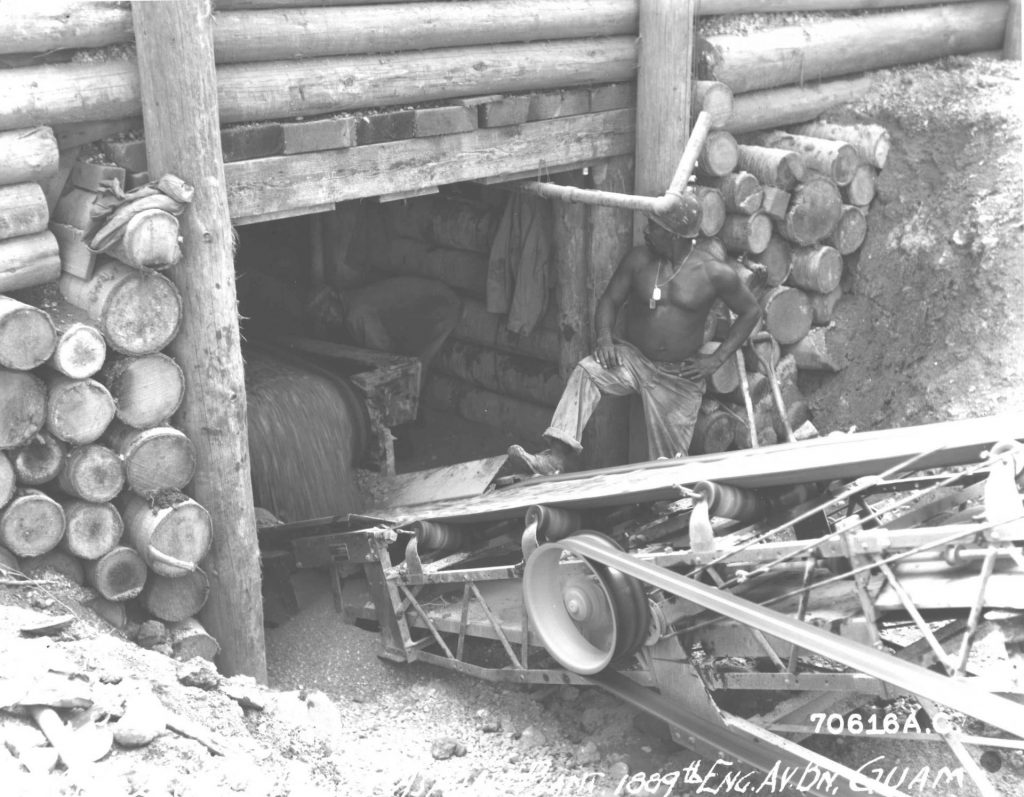

In the face of these challenges, Black service members overcame and persevered, making valuable contributions to the war effort. During the war, more than 100 all-Black battalions contributed to everything from combat duty to medical support, reconnaissance, and of course engineering. Of the 157 separate aviation engineering battalions tasked with constructing and maintaining airfields across the world during the war, 48 of them were segregated battalions. Many of these battalions served in the Pacific or China-Burma-India theater.

“A Timely Engineering Feat”

One such battalion was the 857th Engineer Aviation Battalion, composed of nearly 800 African-American troops that served mostly in Australia, New Guinea, and the Philippines. The bases and airstrips they assisted in constructing proved essential to maintaining air superiority and enabling the island-hopping campaign across the Pacific. No place was their contributions more recognized than during the retaking of the Philippines in 1944-1945.

To retake the Philippines, a foothold needed to be established first on the island of Leyte. Led by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, a charter member of SAME, American forces conducted a grueling amphibious landing and fight across the island. The timing late in the year of the assault forced troops and logistical units to contend with monsoon rains. “The lack of available hardstand areas and access roads under conditions of heavy rainfall continued to dominate the situations and the only potential solution was use of the beach areas reserved for the numerous high-echelon headquarters [for base construction],” Brig. Gen. S. D. Sturgis Jr., USA, recounted in TME years later.

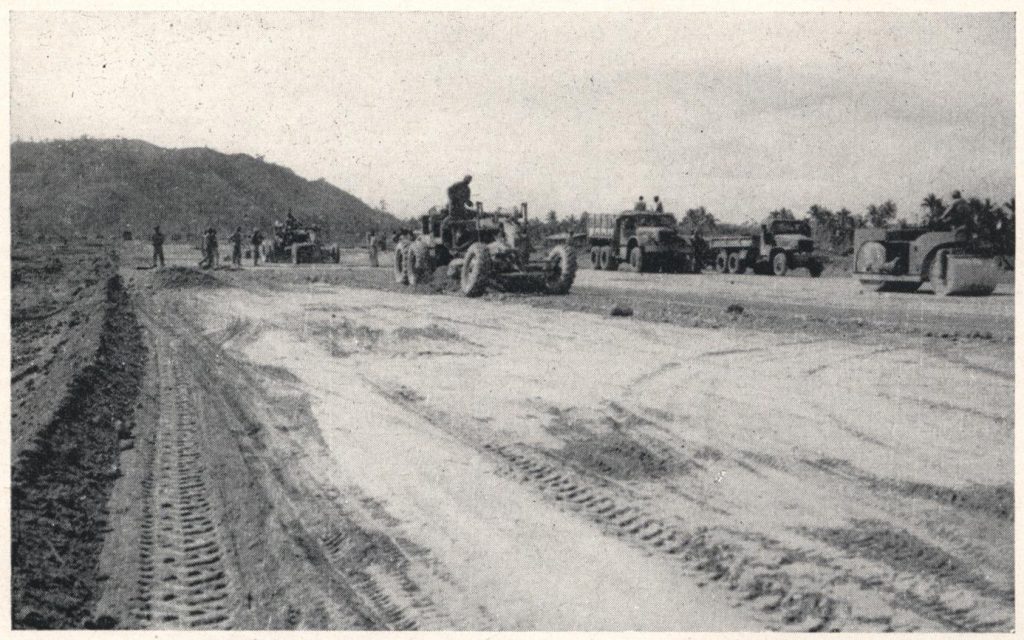

Leyte had been chosen for the first foothold on the Philippines due in part to its strategic location to conduct air missions on the neighboring islands of Mindoro and Luzon in the next leg of the campaign. The 857th was originally tasked with supporting the construction of two airdromes at San Pablo and Buri; however, the sites were so saturated that the decision was made to eventually abandon both sites and move the 857th to assist on the construction of a more location-advantaged airdrome near the village of Tanauan.

This new airdrome was situated on a rocky dome-shaped hill about 250 feet high. Construction on the airdrome began on November 28 and was complete after only 18 days, on December 16. The benefit of the site was good drainage and soil that allowed for construction to continue despite the heavy seasonal rains. The expeditious construction of the airdrome allowed it to be operable for the next leg of the Philippines campaign to retake the neighboring island of Mindoro.

“It is believed that history some day will show that the Project Engineer, Col. W. H. Harrison, his staff, and the Aviation Engineer Battalions assigned the Tanauan Airdrome performed one of the most timely and outstanding construction feats of the war,” Sturgis wrote in TME.

The 857th would continue to make notable engineering contributions in the Pacific Theater for the remainder of the war. After constructing additional supporting infrastructure on Leyte, they moved to the recently retaken island of Luzon. Their final assignment before being deactivated was the construction of living quarters for General Headquarters staff.

Record-Setting Efforts

The accomplishments of the 857th are particularly notable given the incomplete training they were provided. While at Eglin Field, Fla., the battalion was largely used for menial labor and only participated in one field training problem. Likewise, the 811th battalion was only provided slightly more than a month of training before leaving for New Caledonia with the 810th, another segregated battalion, in February 1942.

To say their arrival on the island was rocky would be an understatement. Told that they were destined for cold weather, members of the 810th packed winter uniforms, only to swelter for five weeks in the Pacific heat until they reached Noumea, the port of New Caledonia. It took three weeks after their arrival for their equipment to arrive, during which the engineers endured Japanese bombing runs while unloading cargo ships. When at last their machinery arrived, it needed to then be moved 100 miles over mountainous terrain to the construction site in Plaines des Galacs. Despite these hardships, the engineers managed to construct an operational runway by May 1942, in time for use during the Battle of the Coral Sea.

The 811th was tasked with improving Tontouta, a site 35 miles from the harbor, and their superb efforts would make Tontouta the most important air base on the island. It was here that the 811th established a friendly rivalry with a Seabee unit and set new records for construction. First, they set the island record for B-24 hangar construction. Second, when their unit commander told them they could have a day off for every day they beat the existing Seabee record for the construction of a radio range, the 811th completed it in 13 days under the record. By the end of 1943, the island had five major airdromes and seven satellite fields.

“It is believed that history some day will show that the Project Engineer, Col. W. H. Harrison, his staff, and the Aviation Engineer Battalions assigned the Tanauan Airdrome performed one of the most timely and outstanding construction feats of the war.”

Brig. Gen. S. D. Sturgis Jr., USA

Dedication Rewarded

At the end of the war, aviation engineers had built or improved more than 1,000 airfields around the world, a number that Black aviation engineering battalions had contributed significantly to. Along with their contributions to airfield construction, Black engineers also constructed numerous roads, water points, camouflage devices, pipelines, and bases in all theaters of war, from the Pacific to Burma to North Africa to Europe.

Unfortunately, their efforts would not be properly recognized for years after the end of the war. In 1946, a senior officer panel was appointed by the Secretary of War to compile lessons learned from the experiences of the aviation engineer battalions throughout the war. Mistakenly believing that Black engineer units lacked the technical skills needed for heavy engineering purposes, their recommendation was for the units to be used only “in units wherein labor requirements are predominant.”

Their recommendations, however, did not come to pass. Two years after the report, Executive Order 9981 integrated the services and stated that “there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.” By the end of the Korean War, nearly all the services had completed integration. Thanks to their dedication, African American military engineers helped achieve what was called the “Double V”–victory in the war as well as a victory on the homefront in the ongoing fight against discrimination. This Black History Month, we honor their sacrifices and acknowledge their contributions to the engineering profession and our national security.