Published in 2021, SAME’s Century Book, The Second Century Begins: Preparing for the Future by Building on the Past is the official publication marking the first 100 years of the Society of American Military Engineers. Enjoy this sneak peek of Chapter One, Why We Were Formed. Focusing on the early years of the Society, this chapter follows the young “association of engineers” in the years following World War I as it lays the groundwork for what would become a successful 100-year legacy of industry-government engagement and dedication to patriotism and national security.

When World War I broke out in Europe, it quickly became clear that the new century had brought a new kind of conflict—and that the nature of war had changed forever. It was a conflict that saw unprecedented numbers of military personnel operating over vast areas, and often far from their home countries. At the same time, new technologies, from machine guns and flamethrowers to chemical weapons and tanks, were reshaping the battlefield. Long-range heavy artillery wreaked havoc far behind the front lines. Submarines sank supply transports and troop ships. Aircraft evolved quickly to play a growing role over the battlefields in France, and the concept of strategic bombing emerged as German planes and zeppelins attacked London. And on the Western Front in France, hundreds of thousands of troops moved underground, as the two sides dug in for long, drawn-out trench warfare.

World War I was essentially the first “total war,” where the full weight of national resources was brought to bear against the enemy. It was a battle of numbers, with each side trying to wear the other down with overwhelming volumes of people and materiel. Extensive transportation networks, efficient logistics, and the building and maintenance of infrastructure were critical to success. It was, in a very real sense, an engineer’s war. Courage and discipline were vitally important—but the need to keep people, food, and ammunition flowing to the front lines was critical to victory.

As the American engineers arrived in Europe, they quickly realized that they would have to meet a wide range of engineering challenges, tackling projects requiring the cooperation of experts from multiple disciplines.

When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, the country was not prepared for the kind of conflict it would soon face. The Army Corps of Engineers consisted of just 256 officers and 2,198 enlisted men, and they were organized largely to work on domestic projects. But the military quickly recognized the need to ramp up its engineering capabilities for a war on foreign shores, and through heavy recruiting efforts, more and more civilian engineers were brought into the armed forces. By the time the war ended in November 1918—with the armistice that took effect on the “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”—about 245,000 U.S. engineers had served in France, a significant percentage of the approximately 2 million American soldiers that served there. Another 15,000 were in uniform back in the United States—a reminder that total war relied on engineering talent at home as well as abroad.

THE EXPANDED ROLE OF ENGINEERING

As the American engineers arrived in Europe, they quickly realized that they would have to meet an especially wide range of engineering challenges. They laid roads and railroads across France and up to the front lines, and developed airfields for the aircraft being deployed in the conflict. They built and refurbished ports to handle the growing number of ships carrying soldiers and supplies, they constructed warehouses and depots, and they set up camps and barracks to house soldiers and prisoners. They bridged rivers, dug tunnels, and constructed fortifications and trench works. They set up generating plants and strung electric and communications lines, and they built dams, water purification systems, and conduits for water supplies. They worked in specialized units focusing on everything from chemical weapons and tanks to forestry, camouflage, and sound-and-flash detection to locate enemy artillery.

These engineers tackled projects that could be large and complex, requiring the cooperation of experts from multiple disciplines. They frequently worked in difficult conditions, navigating a French landscape that had been devastated by a conflict that had already been underway for several years and had seen millions of casualties. Through it all, they contended with everything from bad weather and deep mud to shortages of people, supplies, and equipment—all of which required them to improvise and quickly come up with solutions on the ground. And there were the hazards that come with working in a combat zone. Indeed, the first two American casualties in France were members of the 11th Engineer Regiment (Railway), who were wounded by artillery fire in September 1917.

The experience of the Army’s 6th Engineers provides a glimpse of what many U.S. engineers saw at and near the front. A few years after the war, two of its officers recalled their unit’s work prior to a major American offensive in 1918: “During the night preceding an attack, all roads in the sector leading to the front must be made passable for transportation,” they wrote. “Bodies of horses and men must be disposed of, shell holes must be filled, or, if the road has been mined, a new piece of road must be built around the mine, or the hole bridged. Naturally a road is always mined at a fill, making the obstacle as complete as possible and the repair as difficult as possible.”

At the front, the 6th Engineers cut paths through forests, out of sight of enemy gunners, and guided troops through them to their point of attack. “The engineer, in assisting the advance of the infantry and artillery, encounters the usual artificial obstacles—almost always wire and the multitude of natural obstacles such as swamps, rivers, and vegetation,” the officers wrote. “It is in overcoming the latter class, under fire, that the engineer finds his biggest job.”

During the war, American military engineers at home and abroad had to quickly adapt to the emerging battlefield challenges faced by those “over there.” Along with new techniques and innovative solutions, they learned something deeper: the value of teamwork, shared knowledge, and collaboration across organizations and disciplines. The war had meant that thousands of civilian engineers were suddenly working side by side with career military engineers, bringing together what had traditionally been two separate worlds. They learned from one another and drew on their combined experience and expertise—a formula that enabled them to adapt to adversity and tackle challenge after challenge, and to establish an impressive record of success that helped lead to victory in the war.

THE BIRTH OF A NEW ASSOCIATION

After the Great War ended, America’s prewar isolationist political sentiments once again came to the fore. The country began reducing the size of the military and trying to return to what people saw as “normal” prewar life. Just 19 months after the United States had mobilized for the war, tens of thousands of engineers were mustered out of the service and transitioned back to civilian life. But the hard-won lessons of the conflict remained in the minds of many leaders. These people recognized that the old “normal” was a thing of the past, and that wars of the future would require increasing levels of engineering expertise as well as the involvement of both military and civilian engineers. They did not want to risk falling behind in the emerging engineering “arms race.” As an Army Engineer Department publication reported in 1920, “The lesson of the Great War should not be lost, nor should we fail to profit by the experiences which have been so costly. ‘Never again’ should America be found so unprepared for an armed struggle on which her fate as a nation will depend.”

One person who took that view to heart was Maj. Gen. William Black, the Army’s Chief of Engineers, who had overseen the buildup of the military’s engineering capabilities for the war. Black knew firsthand the importance of those capabilities to the war effort—and now, as the drawdown of engineering troops began, he worried about the reduction of that force. As a result, in 1919, he appointed a board consisting of nine officers to consider the creation of an “association of engineers” that could maintain and expand the connections and shared civilian and military knowledge that had been developed during the war. He also sent a letter to all the officers in the Corps of Engineers, asking for their opinions about such an organization. The board reported that the response to Black’s idea was overwhelmingly positive, with feedback coming from both the military and industry.

Those efforts ultimately led to the launching of a new organization—the Society of American Military Engineers (SAME)—on January 1, 1920. As a Society announcement explained, “We are establishing at this time a Society of American Military Engineers. This Society will serve no selfish purpose. It is dedicated to patriotism and national security.” For the first year, SAME operated with a temporary executive staff, and on March 1, 1920, this group adopted a constitution that spelled out the broad goals of the organization, which endure today:

The objects of the Society shall be in the interests of national defense to promote the efficiency of the military engineer service of the United States; to maintain its best standards and traditions; to disseminate professional knowledge concerning development in engineering with special reference to their application to military purposes; to develop between the military engineers and other arms of the service a spirit of co-operation and a mutual understanding of their respective duties, powers, and limitations; and to foster relations of helpful interest between the engineering profession in civil life and that in the military service.

A year after the Society was officially announced, it held its first annual meeting, open to all members, on January 14, 1921, in Washington, D.C. There, Gen. Black was officially elected as SAME’s first President, and a separate board meeting held that day named new officers and executives— all of which was completed in just a few hours.

The Society had a key advantage: an existing publication with an established readership. The Army Corps of Engineers had published its own journal, called Professional Memoirs, since 1909. However, it was having financial issues and new regulations limited government agencies’ ability to publish their own periodicals. So as the Society was being formed, that journal was transferred to the new organization. It was given a broader editorial mission and relaunched as The Military Engineer (TME) in January 1920—meaning that the magazine and SAME were essentially born together. (The announcement of the formation of the Society was carried in the first issue of TME.) The magazine provided a critical vehicle for reaching influential leaders, building membership, and launching a network of local SAME chapters, or Posts. These Posts were quickly established on the West Coast and in the Midwest, Southeast, and Northeast, holding their first meetings in June 1920. By the end of 1920, 16 Posts were in place, and another seven were founded in 1921.

Many influential leaders supported the new Society from the start. Charter members included veterans not only from World War I, but also from the Spanish-American War and the Civil War, with one of the earliest to sign on being Brig. Gen. Henry L. Abbott, USA (Ret.), an 1854 graduate of West Point who went on to serve as a general of Army Engineers in the Civil War. The list of charter members also included Brig. Gen. Charles Dawes, USA (Ret.), who served as Vice President of the United States from 1925 to 1929 and was also Society President in 1928; Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick, USA, the first Chief of the Army Air Corps, the forerunner to the U.S. Air Force; Maj. Gen. George Goethals, USA (Ret.), builder of the Panama Canal; and Maj. Lenox Lohr, USA (Ret.), President of the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry from 1940 to 1968. The list included several distinguished individuals who eventually played prominent roles in the next world war, such as Gens. Douglas MacArthur, Lucius Clay, and John C.H. Lee, who were military governors, respectively, of Japan, Germany, and Italy in 1945.

In just one year, SAME’s membership rolls grew to include more than 3,500 members—a list that included people from across the United States and some two dozen other countries, such as France, Germany, Panama, Australia, Brazil, Korea, India, Mexico, Poland, and the Philippines. That figure was impressive, wrote Gen. Black, but “it is not the number of our membership so much as its quality which affords us great satisfaction.” He added that “so representative, able, and distinguished a body of men cannot be otherwise than a power for good in national and human affairs. The voice of the Society of American Military Engineers will receive respectful attention in all matters pertaining to the national defense and the public welfare.”

THE ENDURING VALUE OF COLLABORATION

From its inception, SAME was designed to transcend boundaries. Membership was open to people from across the military services—including state militias and National Guard units—and to “civilians of suitable technical qualifications, interested in military engineering affairs.”

The goal was to allow civilian and military engineers to learn from one another and broaden their horizons. “The engineer in civil life can learn the practical side of military engineering only by contact and association with those engineers, both civil and military, who have learned the game by actual practice in war or peace,” noted a mid-1920 editorial in TME. “And the engineer in the regular service can avoid the narrow development, which so greatly restricts his usefulness, only by contact with engineers in civil life. Mutual confidence and efficient cooperation are possible only if we are all well acquainted.”

That formula was central to the organization, and it would prove to be indisputably effective in the decades to come. Over the course of SAME’s 100-year history, the challenges facing the United States have changed in many ways. The military has been involved in everything from large Depression-era public works projects at home to global conflict in World War II to guerrilla wars, insurgencies, and conflicts in Asia and the Middle East—as well as infrastructure rebuilding efforts in countries around the world and phase-zero projects designed to help prevent future conflicts.

SAME’s activities have evolved along with those of the military and the challenges to national security. “I have been a member of this Society since its inception,” wrote General of the Army Douglas MacArthur in the mid-1950s. “Its span of years has seen the most remarkable rate of development of civilization the world has ever witnessed. This accomplishment has synchronized with some of the most acute perils the human race has ever known and overcome. In both categories the engineer has distinguished himself and his profession. Not only in what he has done but in what he has prevented from being done, he has established himself as one of the basic pillars of modern society. I have belonged to many distinguished groups but none in which I have a greater sense of honor than in the Society of American Military Engineers.”

Today, SAME’s activities have broadened to encompass everything from identifying national security issues and solutions to enriching the pipeline of STEM professionals, developing engineering leaders, and increasing infrastructure resilience through energy, water, and cybersecurity initiatives. Yet the Society’s underlying core mission remains essentially the same as it was in 1920: to promote cooperation between government and industry and across engineering disciplines, in order to address challenges to the nation’s security.

The founders of SAME believed that World War I was not the “war to end all wars”—and they were right. As they foresaw, the country would continue to need to draw on the collaborative strength of the full engineering community to meet new and complex challenges. This proved to be a valuable insight as the nation saw huge reductions in its military forces between World War I and World War II. With the establishment of SAME, these prescient leaders helped ensure that the United States was, and always will be, ready to meet those challenges.

In 1920, TME assessed SAME’s early success, saying, “An excellent start has been made, and the outlook for the future is bright.” Those words still ring true today, as SAME enters its second century of helping the nation’s engineering professionals keep the country safe, secure, and resilient—and always looking toward the future.

Spotlight on Our Society

In Focus digs deep into singular programs and events from across the Society, shining a light on how SAME is making an impact on developing multidisciplined solutions to national security infrastructure challenges.

-

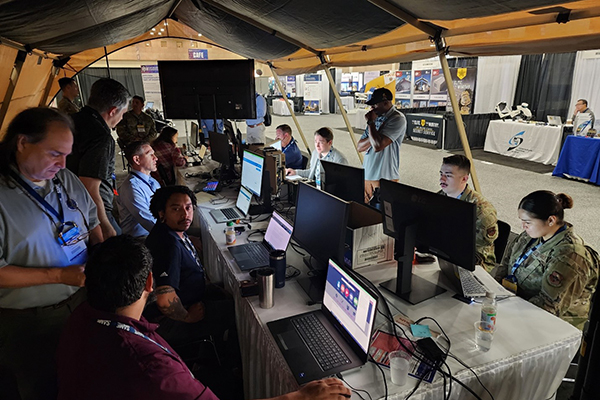

In Focus: Managing Assets At JETC

At the 2023 JETC, geospatial engineers continue the tradition as digital warriors who create the understanding of complex and ever-evolving operating environments. -

In Focus: Preparing for Ukraine Reconstruction

The SAME JECO Community of Interest has been preparing for the eventuality of reconstruction efforts in Ukraine through tabletop exercises, panel discussions, and more. -

In Focus: We Must Go To Them

As part of the We Must Go To Them program, four geographic and culturally diverse SAME Posts jumpstarted outreach efforts in their local AI/AN communities.