Within the vast history of World War II, there are countless stories of individual heroism, ingenuity, and sacrifice. By the end of the war, Hispanic Americans had served in every major theater. They served as infantry, tankers, Marines, pilots, seamen, nurses, medics, and engineers. More than 500,000 of these brave Americans fought from Normandy to Berlin. They struggled to hold islands in the Pacific, checked the enemy in North Africa, and halted the aggressors’ advance in Southeast Asia.

This Hispanic Heritage Month, TME looks back at the sacrifices made by these servicemembers, recounts their contributions to our nation, and remembers their accomplishments.

Street of Heroes

Frank Sandoval, his five brothers, and his four sisters grew up the children of Mexican immigrants. Like so many other fathers and mothers of the time, Edubigis “Ed” Morado and Angelina Hernandez Sandoval brought their family to the United States to escape the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. Their search for safety led them to the small town of Silvis, Ill., in 1917. The Sandoval family made their home on 2nd Street in Silvis, which was just one and a half blocks long.

Frank had just three years of high school behind him when he enlisted in the Army in September 1942. By the time of Frank’s enlistment, two of his brothers had already joined the military. His older brother Emidio was stationed in New York, and Joe would begin his service with the Army’s 41st Armored Infantry Division in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Eventually, all five brothers would find their way into service.

Frank began his own military journey on October 3, 1942. By November, Frank was sent to Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., for combat engineer duty, where he would receive specialized training and given his assignment with the 209th Engineer Combat Battalion, Company C. A year later, in November 1943, Frank and his company found themselves halfway around the world on a mission to coax a road out of the most stubborn terrain on earth as part of the Ledo Road project.

The Vital Lifeline

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan turned its attention on the resource-rich lands of mainland Asia and began its push across the South Pacific into Manchuria, eastern China, Indochina, and Siam. By March 1942, Japan had taken the port city of Rangoon in southern Burma. With this strategic location, the Japanese now had control of the north-south road and rail systems called the “Burma Road” that stretched over 700-mi from the Bay of Bengal to Kunming, China. The Allies’ main transportation artery through Burma and into China had been severed.

With this major supply line to China cut off, and the border to India threatened by rapid Japanese advances northward, a new route to continue funneling critical military and humanitarian provisions was needed to keep China in the fight. Success would require a bold and dangerous plan.

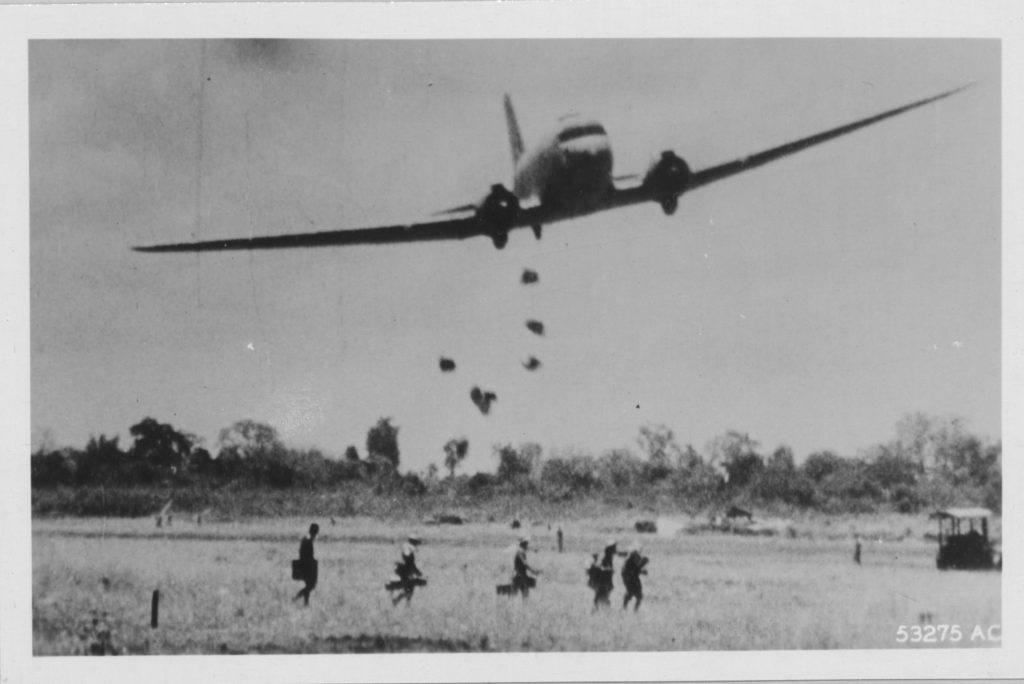

U.S. Transport Command aircraft began ferrying military cargo over the “Hump”—the nickname given to the 500-mi route over the northern Himalayas—from bases near Chabua, Assam, India to Kunming and other locations in Yunnan Province, China. The perilous route required pilots to push their ungainly C-46 Commando aircraft to their limits. Pilots regularly worked 16-hour shifts, sometimes flying three round trips a day. The treacherous routes were flown at altitudes of over 24,000-ft in dangerous conditions. Overloaded planes could be flipped over or find themselves suddenly plummeting or rising 3,000-ft/min as freak 248-mph winds slammed the aircraft. Through the monsoon storms, constant harassment by enemy aircraft, and risky landings on makeshift runways, the pilots of the India-China Wing, Air Transport Command ferried over 650,000-T of cargo over the hump.

This impressive amount of materiel delivered came at a high price. In total, 600 planes would be lost and over 1,000 men killed. To establish a more sustainable and consistent supply chain, a new land route had to be established.

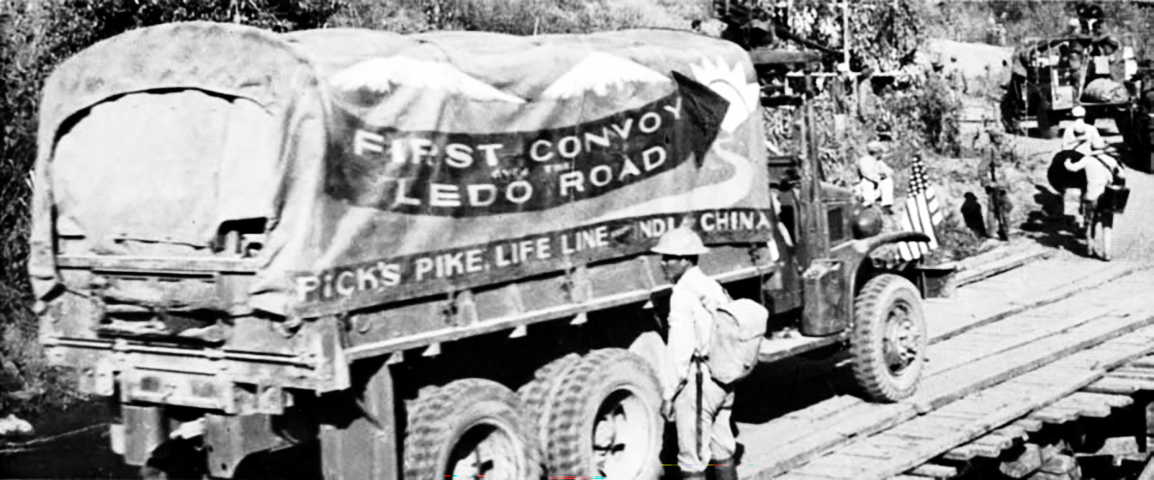

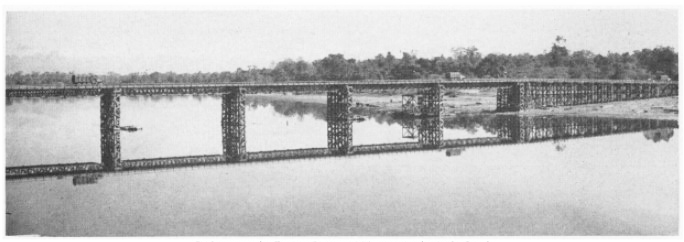

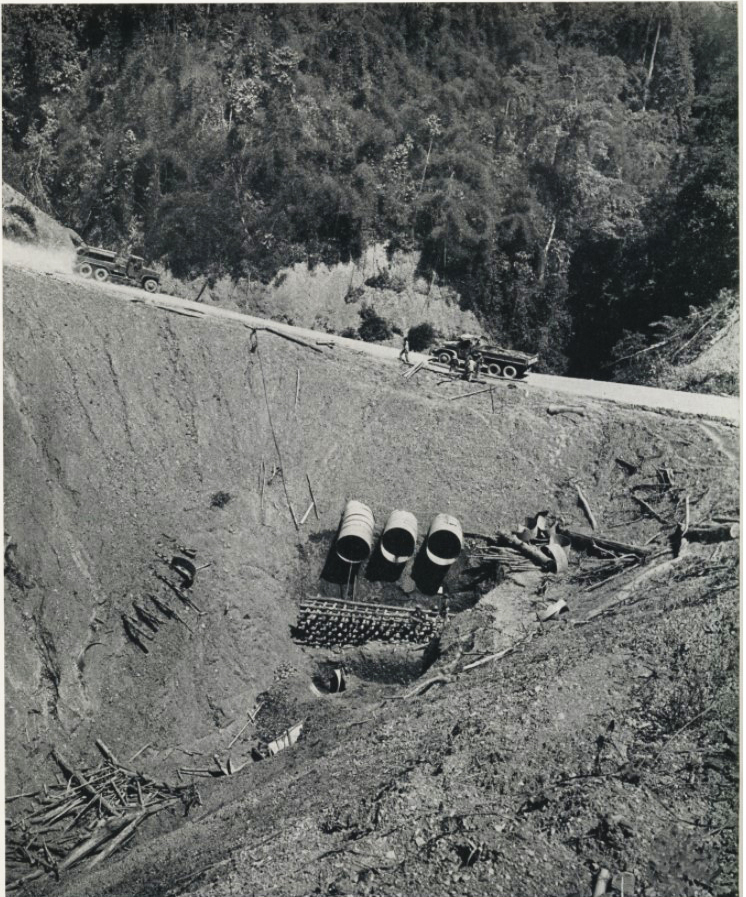

In December of 1942, construction on the Ledo Road began. Spanning nearly 500-mi, the road would stretch from Ledo, Assam, India to Myitkyina, Burma, where it would join with the original Burma Road as it turned northeast into China. It was difficult terrain; the first 275-mi of the road had to be cut through uncharted jungle before winding through mountains, dense swamps, and deep ravines. The job that lay before the American engineers and an army of Chinese and Burmese laborers would be called the greatest engineering project of the entire war.

A Costly Battle

Pfc. Frank Sandoval and the 209th joined this herculean effort in the fall of 1943. Frank and his fellow engineers set about the job of road building, and for many, it was their first time operating heavy equipment like bulldozers and rock-crushers. Constantly on alert for Japanese attacks, the men also battled the choking humidity of the jungle where malarial mosquitoes thrived and monsoon rainfall was so intense that large portions of road could be washed away in minutes.

On May 23, Frank and the rest of his battalion were ordered to prepare for combat duty. Merrill’s Marauders, a fearsome group of jungle fighters, had beaten back the Japanese at the airstrip at Myitkyina, but were in dire need of support. Trading their shovels for rifles, the engineers who had built the airstrip were loaded onto C-47s and sent to defend their work. On June 22, Company C took positions along the banks of the Irrawaddy River to provide fire support and defend the flank as the 3d Battalion of the Marauders moved against the Japanese forces.

A 1952 article in The Military Engineer (Vol. 44, No. 302, November-December 1952), recounts the actions of the 209th, where Company C was engaged in intense battles protecting the airfield near the Irrawaddy River on June 26, 1944. Within a few weeks, the Marauders and the engineers secured the critical airfield and the town of Myitkyina, but unfortunately Frank did not live to see the historical victory that the 209th fought to achieve. His sacrifice, and the many other lives given for the Ledo Road, were not in vain, however. In January 1945, the Ledo Road, now known as the Stilwell Road, was completed and the first trucks reached Yunnan, China on January 28, providing much-needed supplies for the forces there.

The 209th ECB suffered heavy losses of 71 killed and 179 wounded. The 209th was one of the most highly decorated units in the China-Burma-India theater, with a Distinguished Service Cross, three Silver Stars, 33 Bronze Stars, 181 Purple Hearts, and a Presidential Unit Citation.

In the small town of Silvis, Ill., Frank’s childhood street of 2nd Street would be renamed Hero Street by the town. In the one and a half block long neighborhood, comprised of a scant 25 homes, over 100 young men and women would serve in the U.S. Armed Forces—more than any neighborhood of similar size in the United States.

This Hispanic Heritage Month, SAME honors the sacrifices made by Hispanic Americans like Frank Sandoval and their contributions to the engineering profession and our national security.

Celebrating a Century of Military Engineering

As SAME celebrates over a century of dedicated support for our national security, look back through our historical archives at how engineers and the Society have evolved to meet new challenges. TME Looks Back dives into the previous century of engineering history—and what it means for us in the modern day.

-

TME Looks Back: Inspiring Collaboration and Inclusion

In celebration of Women’s History Month as well as the 82nd anniversary of the establishment of the Navy Construction Battalions in 1942, TME Looks Back to an influential moment from 1994 that set the stage for more women to serve as Seabees in the U.S. Navy and as leaders across the deploying engineer units. -

TME Looks Back: A Hispanic Engineer In The CBI Theater

This Hispanic Heritage Month, TME looks back at the sacrifices made by Hispanic servicemembers, recounts their contributions to our nation, and remembers their accomplishments. -

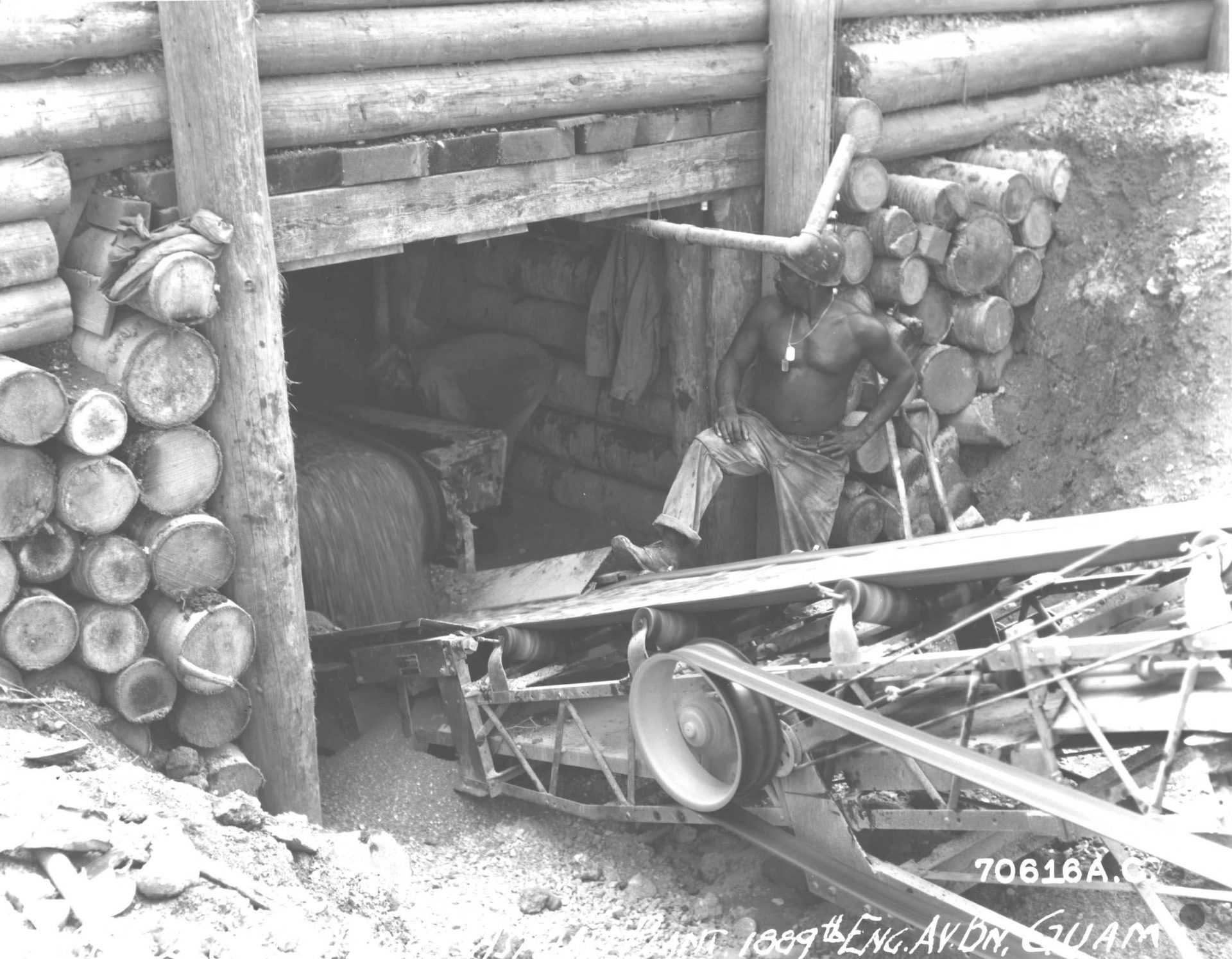

TME Looks Back: African-American Engineering Battalions in the Pacific Theaters

In the face of these challenges, Black servicemembers overcame and persevered, making valuable contributions to the war effort. During the war, more than 100 all-Black battalions contributed to everything from combat duty to medical support, reconnaissance, and of course engineering. Of the 157 separate aviation engineering battalions tasked with constructing and maintaining airfields across the world during the war, 48 of them were segregated battalions. Many of these battalions served in the Pacific or China-Burma-India theater.